It was Universal Studios' fond hope at the time of approval in the late Fall of 1980 that they could make THE THING on the cheap - they were thinking of a budget of Eight Million Dollars Direct ( the actual cost of the film ) which with Indirect studio overhead costs of Twenty Five per cent ( a mysterious calculation we tried to unravel with partial success ) would allow them to reach their target of Ten Million Dollars ( $ 10.000.000. ) Combined. Surely John Carpenter, coming from the thrifty world of Independents, could find a way ? Well no, John Carpenter couldn't and neither could anybody else so we set about trying to come up with a realistic figure that wouldn't give Universal pause...

|

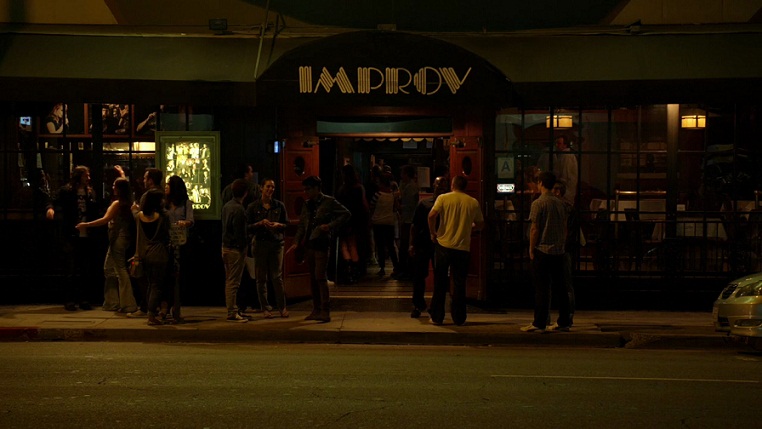

| Night Exterior filmed on stage : THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD |

...The situation wasn't helped when the studios' production department presented their best guess at cost and came up with a preliminary estimate of Seventeen Million Dollars ( $ 17.000.000 ) without overhead, a figure that scared the Executive Flank. Their original plan called for significantly more set construction on stage, including a duplicate Outpost 31 Exterior that was to have functioned for night work only ( the initial thinking was that it would be close to impossible to film on a snowbound location at night ). There was also the large set piece to be built for Bill Lancasters' original Bennings' death on ice sequence, as well as a separate set budgeted for the Norwegian Camp Exterior...

In addition the Studio concluded ( wrongly, as it turned out ) that it would be astronomically expensive to refrigerate their own sound stages, and therefore budgeted a great deal of money to rent a series of Ice Houses ( or large Cold Storage Lockers ) in the Los Angeles Area to accommodate the production. As romantic as the notion was in following in the footsteps of Orson Welles, who used them to great effect on THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, the idea amounted to putting cast and crew in a giant freezer for months along with assorted explosives, goo, and flamethrowers. I remember surveying some of these early on with John Lloyd, but with their low ceilings and cramped conditions we could see the idea was ridiculous...

The studio's original schedule called for a whopping 70 filming days inside somewhere, with an additional 28 days of location shooting figured in. No provision was made for any second unit special effects filming of any sort...

... and, more significantly, Universal had budgeted a paltry Two Hundred Thousand Dollars ( $ 200.000 ) for what they termed "Creature Effects", scattered around the mechanical special effects and make-up departments as well as the optical department in post production.When we told them this wasn't going to be adequate they were genuinely surprised, stating this was more than they had ever budgeted for a monster movie - after all, didn't Universal have some experience in making monster movies ? And, by the way, what was our best guess at the cost of the creature ?

.jpg) |

| John, myself, Rob |

We had absolutely no clue, none. We were in the process of evolving from original designer Dale Kuipers' one piece conception of The Thing ( which used Bill Lancasters' early draft screenplay descriptions of the monster in the final confrontation with MacCready as a springboard ) to Rob and Johns' more deconstructivist model. This was all new - new approach, new techniques, new materials - and there was simply no template, creative or financial, from which to draw. We spent a lot of time explaining ourselves to the various craft unions - the notion that the work would require an overlap, a blending of responsibilities was confusing, and even threatening, to some. Rob, at the tender age of 22, was required to be a politician ( and was pretty good at it ) in addition to all his other responsibilities...

Above all, it required people get used to the idea that, for this movie, the creature would come out of the shadows and be seen. And, at John Carpenters' insistence, everything was to happen "Live, in front of the camera, like a magic show" as he was fond of putting it...

As the bulk of the design and storyboard work was being finalized everyones' combined brainpower came up with a figure of Seven Hundred and Fifty Thousand Dollars ( $ 750.000 ). We were never really comfortable with this - the best spin we could put on it was to call it an "educated guess ". The Studio, wide - eyed at the number of crafts people that were beginning to show up at Universal Heartland, Robs' special effects facility, reluctantly acceded...

.jpg) |

| Dale Kuipers' "original form " concept, suggested by Bill Lancasters' early drafts |

The original budget for cast reflected our thinking of THE THING as a genuine ensemble piece. All Twelve roles were pencilled in at the same figure, which I believe was Fifty Thousand Dollars ( $50.000 ). As we began to lean in the direction of a more established name for MacCready, this figure had to be adjusted. I remember Kurt Russell, commensurate with his status as a rising star, being paid a salary of Four Hundred Thousand Dollars ( $400.000 ).

.jpg) |

| The Outpost 31 Proletariat : all cast members were going to be paid the same |

Production genius and John Carpenters' Better Half Larry Franco took charge of the major trimming. The schedule was slashed by a third - John would just have to shoot a little faster. The duplicate Outpost 31 Exterior was an easy elimination - the company was going to have to tough it out at night on location. Dropping Bennings' original death scene proved to be more difficult. A favorite of everyones', including the Studios', it proved to be one large set piece too many and, at a projected cost of One Million Five Hundred Thousand Dollars ( $1.500.000 ) was reluctantly cut...

.jpg) |

| Larry Franco on set |

My contribution to the proceedings was the suggestion that we eliminate the separate Norwegian Camp Exterior in favor of filming the back of the Outpost 31 set after we blew it up. I remember asking John if he thought he could shoot it without compromise. He thought only for a second and answered " Yes, yes, I most certainly can..."

The Two Hundred and Fifty Thousand Dollars ( $ 250.000 ) savings that resulted was one of the last pieces of the budget cutting pie...

.jpg) |

| Filming the back of Outpost 31 as the Norwegian Camp a day after "the Big Blow" |

When all was said and done, we were approved and began production in August of 1981 at a figure of Eleven Million Four Hundred Thousand Dollars ($11.400.000) Direct. With Indirect overhead costs just under Fourteen Million Dollars ($14.000.000).

The schedule called for a total of Fifty Seven ( 57 ) First Unit filming days - Forty (40 ) on stage and Seventeen ( 17 ) on location, with some additional second unit days figured in. Larry Franco described it as a compromise - more time than John Carpenter usually got and less than he would probably need...

|

| First Day of Production, First Shot |

...but primarily thanks to Larry ( who is the single biggest reason John was able to get what he got on this movie ) we came damn close to holding to this. Despite almost daily hardships and setbacks I remember slipping only a day or so at most while filming on stage and staying very close to schedule while on location in Stewart...

The major overage came, no surprise here, from Robs' Special effects unit. We had effectively burned through the budget by the end of December, with what was turning out to be months of work ahead. John kept backpedalling and simplified requirements where he could - eliminating entirely Nauls' confrontation with a version of The Thing we called the Box Monster after the first try was unsatisfactory, rather than apportioning additional weeks of time to try to get it right, for example - but by then Robs' unit was functioning like a steamroller heading straight downhill, flattening conventional considerations of time and money in it's path. When the final figures were in we doubled the original budget, an overage of Seven Hundred and Fifty Thousand Dollars ( $750.000 ). Things got so tight at the end John was obligated to make a personal appeal for the last One Hundred Thousand Dollars - a luncheon was arranged with Production President Ned Tannen for this purpose, with the money going to finish off a greatly simplified version of the Blair monster...

.jpg) |

| ...for want of another Six months and Five Hundred Thousand Dollars... |

Final cost with overages included : Twelve Million Four Hundred Thousand Dollars ( $12.400.000 ). With overhead a shade under Fifteen Million Dollars ( $15.000.000 ).

And cheap at twice the price...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)